To make a mushroom spore print:

- Find a mushroom. (Obviously.) Fresh, not too young or old, and ideally with a handful of others like it that you can take home, too. If you get especially lucky, and happen upon a group with some as little buttons1 and others as mature mushrooms, take a variety.

Do be a responsible mushroomer and leave a few to propagate their species. If they're edible, and you eat them all, you won't have the same pleasure next year.

- Get some white and black paper. Spores can be all sorts of colors, from white to black and a maddening array of subtly different shades in between. With two different backgrounds, it's easier2 to make distinctions.

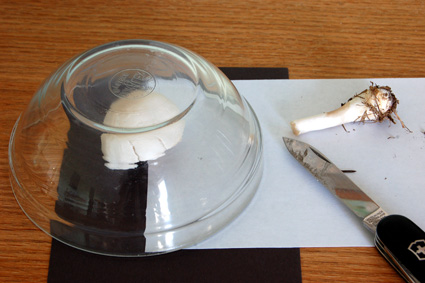

- Place the spore-producing surface above the paper, half on white and half on black. If you can, leave a bit of stalk to elevate the cap above the paper, though it's not necessary. Cover the mushroom with a bowl, wax paper, or some such to keep it from drying out. A dry mushroom won't drop spores.

- Wait. Several hours is good; overnight is ideal.

- If you can, try to peer under the cap3 to see if a print has formed on the paper. You can lift the cap, too, though doing so before it's finished can result in a smudged print. It's still fine for identification, but doesn't look as sharp.

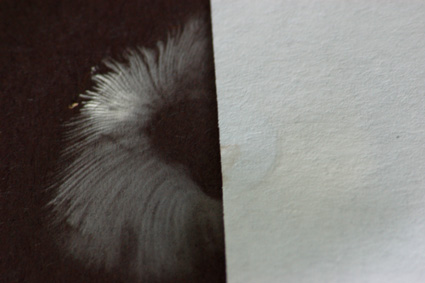

- When it's ready, take the print to a place where you can view it in sunlight. Artificial light sources, such as incandescent and fluorescent, just can't provide the same full-spectral distribution you need to make a crucial distinction.4

- Use that spore print - and other observations - to figure out just what it is that you brought home. And, if you like the print, you can hit it with a bit of artist's fixative and keep it. A good print looks sharp, indeed.

To identify your mushroom:

- Determine which category you should start in. In this book, your options are:

- Split Gill Family

- Chanterelles and Allies

- Gilled Mushrooms

- Boletes

- Polypores

- Tooth Fungi

- Cauliflower Mushrooms

- Branched and Clustered Corals

- Fiber Fans and Vases

- Jelly Fungi

- Crust and Parchment Fungi and Allies

- Puffballs, Earthballs, Earthstars, and Allies

- Stinkhorns

- Bird's-Nest Fungi

- Blueberry Galls and Azalea Apples

- Rusts and Smuts

- Morels, False Morels, and Allies

- Cup and Saucer Fungi

- Earth Tongues, Earth Clubs, and Allies

- Cordyceps, Claviceps, and Allies

- Carbon and Cushion Fungi

- Hypomyces and Allies

Got it? In this case, we've got gills. 90% of the time - probably more - you're here or in Bolete territory. Especially if you're picking things that look like mushrooms. - Split Gill Family

- Work through the key as best you can. It helps to check the glossary for unfamiliar terms, such as: decurrent, amyloid, lamellulae, etc. It's sort of like a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure, where you read through the options, pick the one that suits best, and jump to that number.

"1. Stalk central to eccentric → 2.

1. Stalk absent to lateral → 26."

Off we go to number 2. - "2. Gills attached to decurrent; gills, cap flesh, or stalk exuding latex when cut..."

Nope. Not a Lactarius.

"2. As above, except latex absent; gills white to pale orange; lamellulae few or absent in many species; stalk lacking vertical fibers, snapping somewhat like a piece of chalk..."

Nope. Not near that brittle a stalk.

"2. Not as in either of the above choices, but spore print white to cream → 3.

2. Spore print pink, tan, yellow, or darker → 4."

Down to number 3. - "3. Universal veil slimy to glutinous..."

No universal veil.

"3. Universal veil present..."

Same deal. I'd spotted these in various stages of development, and there's no evidence of one. If it's been raining, especially, there's a chance that a universal veil could have been washed away.

"3. Entire mushroom usually very moist..."

Nope. It's a rather dry mushroom, with a texture like the supermarket button variety.

"3. Cap coated with loose granules..."

Nope.

"3. Cap white, tan, brownish, or reddish, usually distinctly scaly in age; gills free, white, close; partial veil present, usually leaving a ring on stalk; terrestrial, usually growing on dead plant debris (e.g., leaves, needles, wood chips); spores smooth, dextrinoid, amyloid, or inamyloid → Genus Lepiota and Allies."

That's our sample. But for the microscopic characteristics, everything matches. Which is great, because the next choice in the list includes the phrase "other characters exceedingly variable", which doesn't inspire too much confidence. - Skipping ahead to the Lepiota section, there's another Choose-Your-Own-Adventure, starting out with long, precise descriptions. Passing those that don't match leads to two choices: Lepiota naucinoides, edible, and Lepiota cepaestipes, poisonous. Turns out it's the latter, though both could be confused for a deadly Amanita species by a casual observer.

1Or whatever the immature shape happens to be.

2But not always easy. Get used to the differences between cinnamon brown, rusty brown, and ochraceous, for starters.

3Keeping the cap elevated just slightly makes this much, much easier.

4I suggest trying to distinguish between similar shades of brown under incandescent light first, then under daylight. The perceptual difference is striking.

2 comments:

Thank you!

thankyou Brian for your post here; I note no way to contact you to request using your blog to link to in my current blog post.

Post a Comment